Marijn van Putten@PhDniX

Dec 23, 2022

19 tweets

The Quran was canonized around the year 650. After this standard was established, the text underwent no real changes. Any manuscript is word-by-word identical to the other, save for obvious mistakes and a few regional variants. But what about the time before this canonization?

The Islamic tradition tell us that during the time of the prophet, there was some amount of variation between how different people recited the Quran. Not just in its pronunciation, but even in its precise wording. The text was oral, and with an oral text comes oral variation.

The famous hadith known as the sabʿat ʾaḥruf "seven modes" hadith addresses this kind of variation. Resolving a conflict that arose between companions about what the precise wording is of the Quran, Muhammad is said to have told them that the Quran was revealed in "seven modes".

There is a great amount of discussion in the Islamic tradition that discuss how exactly this Hadith should be interpreted. A compelling modern analysis is presented by Yasin Dutton, who interprets this as reflecting the oral variation that existed in the early years of Islam.

Of course it is debated whether the prophet simply allowed for some amount of oral variation (most realistic in my opinion), explicitly sanctioned each variant that would arise, or literally revealed the Quran personally in every single way that people would recite it.

Whatever view you take, we are left with several versions of the Quran, which differed in wording. Therefore, there is no single answer to the oddly specific question: "how many words are there in Sūrat al-Kahf From the first (18:12) to the last (18:26) attestation of labiṯū?"

This is not purely hypothetical. The Islamic tradition tells us about hundreds of readings of companions of the prophet which cannot be unified with the standard text today. This of course makes sense: that standard text did not exist yet at the time.

There are even ample reports that several of the companions had their own personal copies of the Quran. We have quite numerous reports from such copies (especially Ibn Masʿūd's but also ʾUbayy's), and exegetes would sometimes use them to clarify the meaning of the standard text.

In our, totally arbitrary passage, we for example find reported that ʾillā ḷḷāha "but God" in Q18:16 was written as min dūni llāhi "except God" in the Muṣḥaf of Ibn Masʿūd; Something reported, for example, by al-Ṭabarī. So a word more than what we have in the text today.

The fact that exegetes took these texts seriously enough to cite, and they often bring first person reports of their contents, suggests they had access to them. But we don't need to rely on medieval reports to confirm the existence of such companion codices.

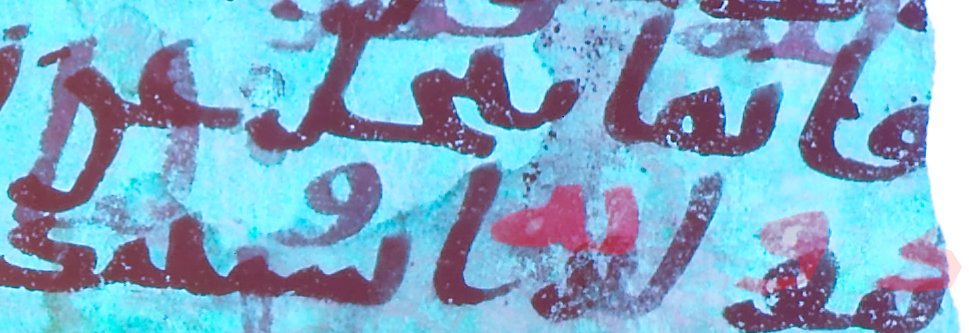

The Sanaa Palimpsest, one of the most valuable manuscripts that we have. The upper text contains the standard text of the Quran. It was written over an original text, which also was the Quran! But not the standard Quran as we know it, but what appears to be a pre-canonical one.

You can still see the traces of the original erased text if you look carefully, and with UV photography that comes even more to the forefront. Behnam Sadeghi and @Mohsen Goudarzi wrote an excellent edition of the folios they had access to. Still the best edition of the text to date.

It just so happens that the portion that was added just so happens to preserve a portion of our -- I assure you, totally arbitrary -- section of the Quran that we were looking at. And indeed we find a couple of variants in the section that affect the number of words in it.

In Q18:16, we see the traces of min dūni llāhi, exactly the variant that was reported for the companion codex of Ibn Masʿūd!

That this variant is found both in the manuscript and in reports for companion codices can't be a coincidence, and points to it being a genuine variant.

In the next verse, Q18:17, we find yet another variant. Where the standard text has minhu "from it", the palimpsest has bayna ḏālika "between that". Again a single word of the standard text corresponds to two words in the Sanaa palimpsest.

In the same verse we find the traces of an additional min dūnihī before the last two words of the verse: waliyyan muršidan. Here it doesn't replace any word in the standard text, it is just two additional words.

So taking the surviving passage in the Sanaa palimpsest and comparing it against what the standard text has, we see the following differences.

Assuming that there were no other variants, counting the words from first to last labiṯū and arbitrarily and totally unjustifiably counting wa- as a separate word and law lā as a single word... you would end up with the number of 313! Which, like 309, has no special significance

For those who think only deities can have passages add up 309 (or 313 depending on the text type) -- or between 278 and 283 if you don't change the rules to fit your conclusion -- I present to you "Not a Wake" which I'm quite sure was written by a mortal.

cadaeic.net/notawake.htm

Marijn van Putten

@PhDniX

Historical Linguist; Working on Quranic Arabic and the linguistic history of Arabic and Berber. Game designer @team18k

Missing some tweets in this thread? Or failed to load images or videos? You can try to .