ɖʀʊӄքǟ ӄʊռʟɛʏ

@kunley_drukpa

@kunley_drukpa

Feb 8, 2023

28 tweets

WHY BHUTAN FORCIBLY EVICTED ITS ETHNIC MINORITIES

In the 1990s, Bhutan underwent a rapid demographic change: In 1985, Ethnic Minorities had been 25-45% of Bhutan’s Population. By 1996, over 100,000 of those Minorities, 1/6th of the Population, had been forced out of Bhutan

WHY BHUTAN FORCIBLY EVICTED ITS ETHNIC MINORITIES

In the 1990s, Bhutan underwent a rapid demographic change: In 1985, Ethnic Minorities had been 25-45% of Bhutan’s Population. By 1996, over 100,000 of those Minorities, 1/6th of the Population, had been forced out of Bhutan

WHY BHUTAN FORCIBLY EVICTED ITS ETHNIC MINORITIES

In the 1990s, Bhutan underwent a rapid demographic change: In 1985, Ethnic Minorities had been 25-45% of Bhutan’s Population. By 1996, over 100,000 of those Minorities, 1/6th of the Population, had been forced out of Bhutan

WHY BHUTAN FORCIBLY EVICTED ITS ETHNIC MINORITIES

In the 1990s, Bhutan underwent a rapid demographic change: In 1985, Ethnic Minorities had been 25-45% of Bhutan’s Population. By 1996, over 100,000 of those Minorities, 1/6th of the Population, had been forced out of Bhutan

These events were motivated by anxiety about Cultural and Demographic Displacement; growing concerns in today’s West. This Conflict is different from other Ethnic Conflicts though in that Bhutan largely evicted its ‘problematic’ population and has mostly flourished since doing so

The Ethnic Minority population was ‘problematic’ because it increased so rapidly in the decades prior to the 1990s that the Cultural and Demographic issues that increase caused caught the Bhutanese completely by surprise. The consequences were so apparent they couldn’t be ignored

The Majority Native Ethnic groups in Bhutan are the Ngalop and Sharchop, Tibetan Peoples speaking ‘Dzongkha’, who migrated to Bhutan in the 9th Century and established the Culture and State Modern-Day Bhutan exists in continuity with. Their religion is Vajrayana Tibetan Buddhism

The Ethnic Minorities in question were the Nepalese Bhutanese, or ‘Lhotshampas’. They were an Ethnically Nepalese people, practicing Hinduism and with their own language, who existed in valleys around Bhutan as a part of the Greater Nepal region in that part of the Subcontinent

During the British Raj some Nepalese began to migrate to the Southern lowland border regions of Bhutan - areas that were mostly uninhabited and far from major centres. The Nepalese were low in number and isolated enough that the migration was not then considered too objectionable

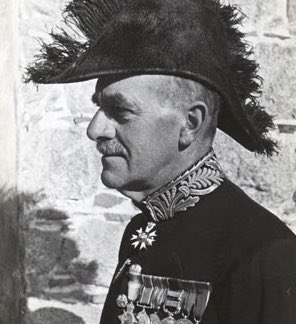

In the 1930s more Nepalese Migrants were encouraged to settle in Bhutan for the purpose of collecting tax revenue from them. As the population grew British Officials, like Sir Basil Gould, warned it was unwise to settle more as they would be difficult to evict “if the need arose”

When the Subcontinent achieved Independence, expatriate Nepalese groups formed the Bhutan State Congress to represent their ethnic interests in Bhutan. The Bhutanese diffused the agitation through protests and concessions for Nepalese representation in their National Assembly

However, Nepalese numbers continued to swell and in 1958 a Citizenship Act passed granting Citizenship only to Nepalese who could prove they had been in the Country for at least 10 years prior to 1958. Nonetheless, their population continued to increase through informal migration

In the 60s and 70s, Bhutan undertook huge infrastructure development drives, increasing the need for labour. More ethnic Nepalese migrated to Bhutan for work - and there were no real formal checks or controls on their doing so, so the Nepalese population swelled even more

By the 1980s the Government became aware of not just the large increase in Nepalese in Bhutan, but lack of integration into Bhutanese Society of even Long-Term Migrants. There was a fear of growing Nepalese Chauvinism, and migrants came to be considered a threat to national unity

The Government promulgated directives seeking to preserve Bhutan's cultural identity as well as to formally embrace the citizens of other ethnic groups in a "One Nation, One People" policy. The culture to be preserved would be that of the majority Native Bhutanese groups

Bhutanese Citizens were required to wear a national dress and follow an etiquette code on penalty of fines. Dzongkha was to be the sole national language. Nepali was discontinued as a subject in the schools. The measures were roundly criticised by Human Rights Groups and Nepalese

A 1985 Citizenship Act restated the 1958 Act. 1958 was the cut-off, Nepalese who could not prove they had lived in Bhutan prior to 1958 were Illegal Immigrants. When a 1988 Census suggested Nepalese could be up to 45% of the population, the Government began inducing them to leave

The additional institutional attacks coupled with the cultural directives began surfacing as ethnic strife directed at non-Nepalese in Nepalese areas. The King, the ‘Druk Gyalpo’, was again accused of cultural suppression and human rights abuses by domestic & international groups

Anti-Government protest marches involved more than 20,000 participants, including some from a movement that had succeeded in coercing India into accepting local autonomy for ethnic Nepalese in West Bengal - who then crossed in Bhutan. Southern Bhutan became a hotbed of militancy

Into the 1990s, the Ethnic Conflict escalated. The Socialist Anti-Monarchist Nepalese Ethnic Interest Bhutan People’s Party, backed by Communist groups in Nepal proper, began organising mass protests - clashing with the Army. It was designated a terrorist organisation

It began arming villagers with rifles, muzzle-loading guns, knives, and homemade grenades – and launched raids on villages in Southern Bhutan, disrobing people wearing traditional Bhutanese clothes; extorting money; and robbing, kidnapping and killing people - reportedly hundreds

Low-level Ethnic Conflict became a feature of life in parts of Bhutan. Along with the violence above, vehicle hijackings, kidnappings, extortions, ambushes, and bombings took place, schools closed and post offices, police, health, forest, customs, and farm posts were destroyed

Foreign Nepalese Groups began lobbying for the establishment of multiparty democracy in Bhutan. Others demanded the Bhutan People’s Party flag be flown on administrative buildings in Nepalese areas - and that culture laws be repealed for the Nepalese under threat of more violence

The Druk Gyalpo decided to crack down on the conflict - ordering more regular censuses, improved border checks, and better government administration in the southern districts. Some Native Bhutanese formed citizens' militias in October 1990 as a backlash to the demonstrations

Internal travel regulations were made more strict with the issue of new multipurpose identification cards. More importantly, the deportation of those Nepalese considered illegal was more consistently enforced - and more and more began to be deported

In 1992 there was another large flare-up in interethnic conflict prompting a peak in Nepalese departures, either through deportation or voluntarily to escape the violence and cultural conditions, totalling over 100,000 departures by 1996 - then some 1/6th of the entire population

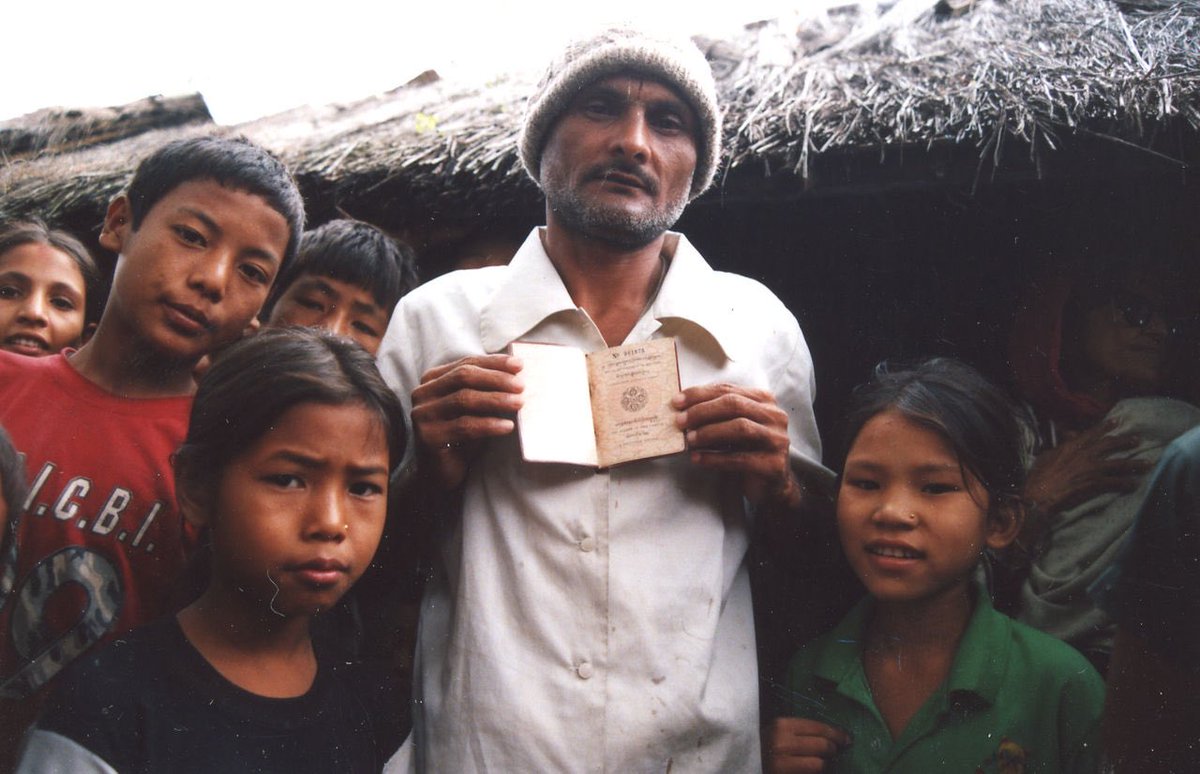

One of the most consequential policies was the unofficial forced evictions by the Bhutanese military, who made significant numbers of Nepalese sign ‘Voluntary Migration Forms’ stating that they had left Bhutan willingly and renounced claims to Citizenship

In all, over the course of the years spanning 1985-96, the policies reduced the Nepalese population to some 10-12% of the population, down from anywhere between 25-45%, most remaining being concentrated in Southern Regions and increasingly assimilated through the cultural laws

Most of the ejected Nepalese now live in Nepal proper as well as India and Western Countries. Most of the ‘Bhutanese’ you meet in the West, if you do meet them, will be Nepalese. That diaspora, as well as many Human Rights Groups, continue to lobby for their cause to this day

Partially as a result of these experiences Bhutanese Policy has for the past few decades been very self-consciously directed at Cultural Preservation. The Culture Laws still exist and heritage institutions and customs are emphasised; in education, religion, architecture and so on

Nonetheless, Bhutan has developed and modernised post-evictions. Bhutan has low crime, high social cohesion, high standards of cleanliness and public conduct, green initiatives, good healthcare and, according to its own metric of ‘National Happiness’, a generally ‘Happy’ populace

ɖʀʊӄքǟ ӄʊռʟɛʏ

@kunley_drukpa

ʟᴇᴠᴇʟ-ʜᴇᴀᴅᴇᴅ ᴀɴᴅ ᴄʀᴇᴅɪʙʟᴇ ᴀᴄᴄᴏᴜɴᴛ || 𝙋𝙧𝙚𝙨𝙨 𝙎𝙚𝙘𝙧𝙚𝙩𝙖𝙧𝙮 for the ℝ𝕖𝕡𝕦𝕓𝕝𝕚𝕔 𝕠𝕗 ℂ𝕙𝕒𝕕 འབྲུག་

Missing some tweets in this thread? Or failed to load images or videos? You can try to .